On the value of double negatives (series: notes to myself)

I grew up as a classic logician. "Classic", not as in "typical", but as in "logic based on the classic assumptions of the principle of bivalence and the law of excluded middle".

Everything used to be either true or false. If something was not true, then it had to be false, and of course vice-versa: p or not p, nothing else, with not-not p just being equal to p.

Disproving not p was equivalent to proving that p. If you think of it, it is quite a smart but strange way of reasoning. Like proving that you are healthy by assuming that you are sick, then running a whole series of deductions, showing that they all lead, inevitably and necessarily, to impossible conclusions, and hence inferring that the premise must be false, thus finally concluding that, since you are not sick, you must be healthy after all. The trouble is that you still have no idea about how or in what sense you may be healthy.

For related reasons, when I was young, I was not fond of double negatives. For it seemed to me that "it is not untrue" was just a verbose way of saying that "it is true".

It was the elegant and rigorous beauty of an Aristotelian world. But, everyday life is not binary, and bivalence is a poor guideline. Double negatives are important. For you learn, with time, that someone who is not unfriendly may not be affectionate either. You come to understand that a behaviour that is lawful would be slightly suspicious if it were described as not unlawful, a bit like an arrow that hits the bull's eye is not really an arrow that just did not fail to miss its target. Not to speak of the English language, in which double negatives have a special function, which is to understate: a movie one dislikes is "not great", a good piece of advice is "not unconvincing", an interesting point of view is "not to be underestimated". People are never good at something, they are not bad at it. They are never right, they are not wrong.

Through the years, I learnt to appreciate and cherish double negatives and their more nuanced, gentle, careful lack of black-or-whiteness. They leave room for readjustments and refinements, rectifications and revisions. They facilitate agreement. They do not antagonise. So we can both concede that a friendship is not unfixable, even if we may have very different views about how damaged it is and what it may take to fit it. Someone is not an idiot, some food is hardly unpalatable, a present is not devoid of some charm, a location is not too far... not a genius, not delicious, not perfect, not near... but still within the realm of the acceptable, agreeable, shareable. There are no winners, just not losers.

The art of double negatives is not to be scoffed at, especially in any convivial and collegial context, when dialoguing with people you do not know too well may require not negligible efforts to be cordial and urbane. But, above all, it is an epistemological stance. It is a way of looking at the world per via negativa. Like in the case of God's attributes, we do not dare to say what the case is, but only what it is not. Thus, in the tradition of apophatic theology, God is not evil, is not unfair, is not unkind, and so forth. What God's goodness, fairness, or kindness may be, the theologians refuse to say, but they know what they cannot be.

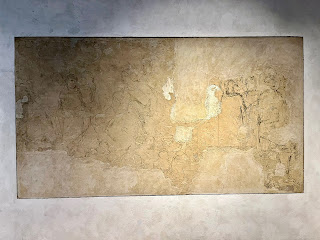

And so we leave behind bivalence and reassuring dichotomies. We enjoy double negatives and do not confuse contradictions (the moon is or is not a goddess) with inconsistencies (the moon is a goddess or an angel). We learn that no gesture is too small. No behaviour is utterly irrelevant. No word can be meaningless. No action lacks consequences. We lightly touch the contour lines of our lives, their environments and circumstances. In the debate between drawing and colouring, our apophatic minds double-negate more like Poussin and less like Rubens: we do not colour the world with our knowledge, we draw lines around it. It is only our experience that is full of reality. We live like Venetian painters, but we understand life like Florentine ones.

Comments

Post a Comment