On Pascal and the door of a Church (series: notes to myself)

We live in a tiny village. Green fields and trees anywhere you look, apart from the local Church and its graveyard, our quiet neighbourhood.

The other day I went to visit it.

I had been planning to meditate inside it, surrounded by symbols, evidence of other people's faith, of their beliefs in transcendence and supernaturalism. A step on Pascal's road, I had thought. Only, in my case, to the re-acquisition of faith, not its acquisition or protection. Keep trying and you will believe, apparently. Well, it turns out to be way more difficult in practice than when you read it in a book. It feels like wanting to believe that the world is different from what it screams to be: messy, accidental, random, chaotic, godless, so pervasively and bottomlessly historical.

I thought I could get inside, in the silent space of the navel of the Church, spend a moment reflecting, and maybe record some thoughts, like I'm doing now. While walking to the Church, I even wondered whether some locals, finding me there, could mistake me for a believer, an error which would not offend me, and I would not mind leaving unrectified.

While going there, I realised that maybe I should have brought something to write. The same locals might judge my using a phone disrespectful. Technology takes so much longer to infiltrate our religious practices than other corners of our lives. Their delicate balance and power to protect and reinforce our beliefs lie in their appearance of immutability: the time must be always, and the place must be everywhere. Religious practices that change with the change of technology would start looking suspiciously immanent, historical, and human throughout. We have forgotten that there are no Abrahamic religions without our invention of writing. How long did it take for bells to be adopted by the Church? And candles? By now, I have seen many electric ones, visiting churches around the world. I guess electricity has finally become as old as writing, bells, and wax. And I bet one day we shall have plenty of digital practices. Maybe you will be able to pay more to turn on some beautiful LEDs or some special 3D effects under your favourite saint. But not now; they would look too modern, too time-bound, too human, too contingent. I keep walking and think it's almost a test for technology. If you can finally use it in a religious context as something normal, then that technology is no longer new or emergent, but a common, trivial, daily, ordinary, part of the world we take for granted. One day, there will be AI apps in religious practices. But not now. Anything digital would remove that patina of antiquity that helps faith to protect its fragile roots in our minds. I take a mental note. Here is another book I shall not write: on the history of the adoption of technology by religious practices.

But it was too late. I was almost there and did not feel like walking back to look for a pen and a piece of paper. I thought that, in case, I could always sit in the back, and be careful with my phone.

The first gate was open and I got into the garden and the graveyard. I'm not sure having the cities of the dead built away from the cities of the living is a good idea for our sense of mortality, of belonging to the universe. We have been hiding death for too long in too many corners of the world. It's good to walk among tombs and crosses, old names on stones erased by the rain, and grass growing gently between people who are no longer.

The second gate was also open. It leads to a smaller garden and the porch of the Church. It is the last place of the profane. Embraced by two sides and a roof, you try to shake the rain off your umbrella, clean your shoes, lower your voice, collect your thoughts, turn off the world, and get inside yourself by getting inside the building. It is a small interface to the sacred, where a rite of passage is subconsciously played. It's a threshold, no more than a few feet wide, but enough to make you feel that you are stepping into holy ground, into the house of God, into a place where other rules apply. On the side wall of the porch, I read the hours of religious services. And there was an old, discoloured poster, by an unreadable charity, an urgent call for some action that must be taken now, or it will be too late. All indexicals, so the "now" is still now and the "too late" is luckily postponed forever.

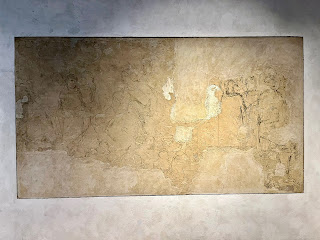

Two gates out of two, and only one door to go. I felt reassured. I turned the handle. I pushed. Gently. Then more firmly. The door, made of solid and well-oiled oak, heavy, thick, and rather low, its irons bits black and shiny, was locked. The obstacle did not give in. Mistrust, I guess. People worried about vandalism, theft, or something less obvious but equally sacrilegious.

Not the day I will re-acquire faith, I thought. Not "now", contrary to what the old poster with some crying children on my right was urging. Maybe it is too late after all. Perhaps faith will visit you only once at most, and having been incapable of holding on to it, its disappearance will be irreversible.

I thought about taking a picture of the times of the mass on Sunday. But I cannot be in the Church with other believers, while they are believing. It would feel like joining a community of druids during some solstice, or on a particular day for the full moon. It would be disrespectful. Moreover, their prayers and practices would only reinforce my doubts. A broken bone needs rest, not more exercise. The re-acquisition of faith, if possible at all, cannot happen by forcing unbelievable beliefs through the throat of the wondering, who is also wandering away. Pascal was wrong.

And so I walked back home, a short distance in steps but long in my mind. Having already forgotten when the Church will be open again.

I would remember Saint Theresa of Avila's words. We don't need to go to a church to search for faith, just humbly communicate with our Saviour...our natural spirituality is god-like:

ReplyDeleteChrist has no body now, but yours. No hands, no feet on earth, but yours. Yours are the eyes through which Christ looks compassion into the world.Yours are the feet with which Christ walks to do good. Yours are the hands with which Christ blesses the world."

This is a beautiful reminder to us about where peace comes from. So often when I witness suffering and tragedy, I find myself saddened by my helplessness. What can I do in the face of such pain and loss? Only something very small. It may never reach those in need directly, but it could reach someone else in need--someone in my own community. It could be the difference between a sense of belonging and a sense of isolation. This beautiful quote echoes the prayer of St. Francis: Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

https://www.coraevans.com/blog/article/14-Of-The-Most-Powerful-Peace-Quotes-From-St-Teresa-Of-Avila

Interesting reflections. It is indeed very annoying when the doors of old churches are locked: a stupid and self-contradictory policy.

ReplyDelete