(revised on Medium) On being immortal (series: notes to myself)

I grew up with two conceptions of immortality in my mind. It took me a while to realise that they shaped my behaviours and my choices. My identity. Neither turned out to be credible. But both were useful, for they taught me a lesson.

As a Catholic, I was brought up believing in a dream. I was immortal. Not backward, for I was born. But forward, because I would not die. Actually, this is not the dream, for it may be the worst of all nightmares. It is the second part that turned it into the best deal ever. I was taught, since I can remember, that if I behaved decently and repented about the rest, I was going to live a life of heavenly bliss forever, and ultimately resurrect, just the way I was (or even better), and join all the people I had ever loved and indeed billions more.

As a kid, I worried, not deeply yet frequently, about eternal damnation, the nasty side of being immortal. Speak of side effects! Better be annihilated, I calculated, than suffer horribly forever. And sometimes I also worried about missing people who may not make it. I knew what I had to do, but what if my best friends ended up on the wrong side of the divine divide? I would have never met them again. I pictured myself alone, in the dusty courtyard behind the church, nobody to play with, baking alone under the cicadish sunshine of an endless Sunday afternoon, looking at the plastic football like an empty planet. The priest suggested a solution: pray for your friends, he said. It may help, he reassured me. It made sense. Well, contextually, it did.

A good eternity was a matter of personal effort, mostly in avoiding sins, not making a mess of my life, being a nice person, and making sure everybody else I liked would join the ultimate party. Success did not depend on anybody else but me. It was entirely my choice, and a choice I could make, no matter the circumstances. I would be judged fairly and knowingly. It was only my responsibility, regardless of who did what around me, when, or how. Want it enough, and eternal happiness was yours. Meritocracy at its best, with a top prize for anyone trying hard enough. I liked that a lot. Heaven was a self-made boy's project. I was going to make it a great success. In fact, I was going to overdo it. I was going to be a saint. Just in case.

But then I grew up.

And while I was losing my faith through a long, slow, painless and meandering erosion that did not become obvious until much later, like a shell turning into sand one gentle wave at a time, I was taught that immortality is not of this soul or body, but of your deeds. That it is based on memory. I was going to die, of course, because entropy was the only omnipotent force in the universe, and it had no mercy. But I had a chance to be remembered forever. It did not matter that my body would soon rot. That I had no immortal soul. And it did not even matter whether my deeds would be the worst or the best. They just had to be memorable. An Oscar, a Nobel, a Gold Medal at the Olympic Games, a Fields Medal, a Pulitzer Prize, ... or the most heinous crime, a genocide, a revolutionary assassination, a terrorist attack, ... anything... because everything depended just on how deeply and permanently I was going to engrave history. This sounded more realistic. Indeed, more classic, because the Greeks and the Romans I was reading at the time often seemed to suggest this much. There was no transcendent heaven. Immortality was an entirely immanent business. It was Leonidas'.

As a teenager, I wasn’t too happy about the bargain. You got so much less for so much more. Eternity had become an individual trace, a permanent scratch on history’s stone. But a very hard goal to achieve. It's much easier to be sinless and go to heaven than to make history and be remembered. And I thought it was too passive. I was not going to be there to enjoy the eternal memory of myself. Besides, now there was nothing I could do for my friends, apart from hoping that they too would leave some lasting record somehow. It was a second-class eternity, difficult to get, enjoyed only in absentia, and too timely bounded. Even if one could be remembered for as long as human history could, I knew this too had a limit. It was a merely human eternity. One day, in five billion years or so, the sun will go, and unless we will have established colonies elsewhere, any earthly immortality will come to an end - I reasoned, slightly disappointed. I consoled myself by thinking that at least it was historical immortality. Yes, the end of history would mean the end of me, if I managed to do something so significant to be remembered for as long as there was human memory in the universe, but there would be nobody around to notice. I would not be forgotten because there would be nobody who could forget me. I would disappear with the last record. I would finally die, but like Samson, under the collapsing temple of human existence in the universe, with everybody else. I would die with memory's death. I liked that. It had a sort of logical elegance in it. It seemed quite heroic. Tragically. Biblically.

But then I grew up a bit more.

And I realised later in life the meaninglessness of my two eternities. One seemed more and more just a childish fancy. Unregainable. It had the advantage of making immortality achievable, and not dependent on anyone but me and a judge fair by definition. But it required a whole metaphysics that made no sense. The other had no such cost. No paradise and hell, no soul or God, no final judgment involved, no resurrection of the body. But it exacted a different, steep price: not just the Herculean effort to leave a mark, but the unpleasant reliance on others and their whimsical tastes, their feeble options, their fashionable interests, to be remembered at all. Their willingness to notice me and keep their memories of me alive, renew them generation after generation, transmitting the record faithfully, omitting no crucial details, adding no apocryphal stories, through more millennia than I could count. I was asked to do something extraordinary but left in the hands of unreliable, messy, perhaps even unfriendly scribes, for that to count at all. Eternity was theirs to give, not mine to conquer. Being remembered by humans seemed to be so much more difficult than being sinless or at least very sorry in God's eyes.

An inexistent Heaven through self-reliance, or a fragile Mnemosyne through others' whims. I did not like the alternative. But I learned something from both.

Today, I know that I am not and cannot be immortal. That nobody and nothing is or can be. That everybody and everything I love will die forever, permanently and irreversibly inexistent, and I shall never see them again. That, ultimately, life on this planet will disappear like a shadow under the sun. Trivial truths, obvious to anyone, but it took me time and courage to absorb them. And even more to live according to them. To be honest, I'm still working on them. There is no eternal Heaven. And all that remains are some memories of us that will fade more quickly than the ivy grows on the walls of a tombstone. There is no lasting Mnemosyne. She is a tricky goddess, quick in changing preferences, and not half as reliable as we would like her to be.

But despite the absence of Heaven, I still appreciate the self-reliance that it taught me and a sense of standalone justice that now has no supernatural justification, just itself to support itself. And from the untrustworthy Mnemosyne, I know that what matters is how I live, not my inexistent soul or my transient body. The importance of a life lived justly: the hollow eternities have taught me this much, and it's not too bad. For while they disappeared, they left behind some dust of their timeliness. A lesson about a different conception of infinity. Not the boundless kind, like the natural numbers that grow forever, year after year. But the endless kind, like the moments between the day I was born and the day I shall die, a finite segment made of infinite points. This is the eternity that I was gifted (Hegel was right, an infinity of +1 is a bad one). Not wasting it, thinking of Mnemosyne without trusting her, and not expecting anyone else to make it worth living but myself, remembering a Heaven that is nowhere to be found. Not to live as if I were immortal. This is the lesson I learned from my two young immortalities.

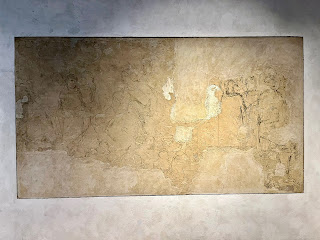

Picture: Roman sarcophagus, collection of the Bank of Italy, Rome.

PS "Notes to myself" is available as a book on Amazon: ow.ly/sGyh50KfRra

Comments

Post a Comment